Kenjiro Nomura’s art ranges from pre-war impressions to post-war abstractions — and images from inside WWII internment camps.

EDMONDS — The first solo exhibition of Kenjiro Nomura’s paintings in more than 60 years is showing here.

The Japanese-American left a record of more than 100 paintings and drawings from his time in World War II internment camps.

But Cascadia Art Museum’s “Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey,” on display through Feb. 20, also features the painter’s pre-war impressions and post-war abstractions of Northwest cityscapes and farmscapes.

“I didn’t want to revictimize him,” museum curator David Martin said. “I don’t think he’d want to be remembered as a victim. Although the internment works are part of his legacy, I wanted to focus on his works as a free man. But we do have some of his internment works included because it’s important. We can’t forget what happened.”

Cascadia’s accompanying catalog — with the same title as the exhibit — was written by art historian Barbara Johns, with a contributing chapter by Cascadia’s Martin. He wrote an essay called “Bridges to Modernism.”

The exhibition of about 60 paintings is a partnership between Cascadia Art Museum and Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

Nomura’s family immigrated to the U.S. in 1907, settling in Tacoma when he was 10. In 1916, Nomura moved to Seattle and signed up for lessons with the Dutch painter Fokko Tadama (1871-1937), also an immigrant, who taught him Western art techniques.

Nomura adopted an impressionist style in the 1920s. His paintings were shown at Seattle Art Institute’s “Northwest Annuals” and University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery. He mentored artists including George Tsutakawa, Paul Horiuchi and John Matsudaira.

When the Seattle Art Museum opened in 1933, its first solo exhibition was of Nomura’s work. As his reputation spread, he showed at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

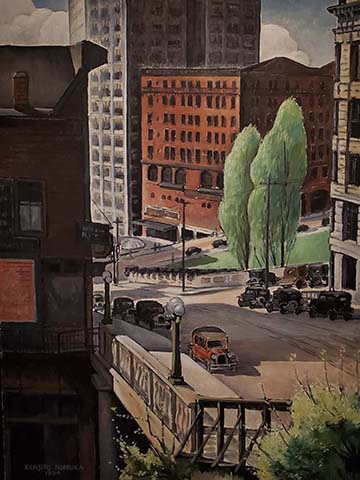

In the 1930s, he was painting American scenes for the Public Works of Art Project — a predecessor to the Works Progress Administration. He gained recognition for his scenes of downtown Seattle, Nihonmachi (or Japantown), which is now Seattle’s International District, as well as Seattle area farms.

Martin’s must-see at the Kenjiro Nomura exhibit is “Yesler Way,” one of his PWPA art projects from 1934. Cascadia’s curator said it makes his top 10 list of Northwest paintings from the era.

In 1942, Nomura and his family were incarcerated at the Puyallup detention facility and Minidoka confinement camp in Idaho. He worked as a sign painter in the camp, which allowed him access to paint and brushes. He painted or sketched on whatever materials were available.

“His internment works are actually scenes of everyday life at Puyallup and Minidoka, so they’re not what I’d call depressing,” Martin said. “They’re kind of what he was doing with his oil paintings, depicting life around him, just this time life around the camps.”

A year after their release from detention in 1945, his wife killed herself. Nomura’s peers — perhaps Tsutakawa, Horiuchi and Matsudaira — encouraged him to pick up painting again to help him through Fumiko’s death. It’s around this time he developed a new abstract style.

Nomura died in Seattle in 1956. After his death, Nomura’s work was shown at the Seattle Art Museum in a solo exhibit in 1960, followed by group exhibitions at the Japanese American National Museum in 1997 and the Seattle Asian Art Museum in 2011.

Martin met Nomura’s son, George, in 1986. He helped George restore one of his paintings of the camps during World War II. That painting “Gymnasium,” in oil from 1945, is on display at Cascadia Art Museum.

“I had never heard of the Japanese internment because I grew up on the East Coast,” Martin said. “I was so shocked when he told me about it. I couldn’t believe that this happened.”

Although George and Betty Nomura died before they could see “Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist,” their daughter — Kenjiro Nomura’s granddaughter — attended the opening on Oct. 21.

“It was really emotional for me because my mom and dad have both passed away,” Lisa Nomura Kidwell said. “I know they really wanted to be there for that, and they weren’t, so that was very sad for me. But at the same time it was a happy thing because I got to be there and it was a huge honor to be able to be there to represent my family.”

Kidwell, 51, never knew her grandfather. He died 14 years before she was born. But she knows his paintings.

George and Betty Nomura had a collection of his Northwest cityscapes and farmscapes on their walls in Covington. Now she has “Dragon Dance” and “International Festival,” two of Nomura’s abstract paintings from the 1950s, at her house in Bonney Lake.

Kidwell said she didn’t learn about the Japanese-American internment camps until 1990, when her family received a reparations check.

“My dad never talked about it, they never taught it in my high school in U.S. history, so I was very shocked to find out about that,” she said. “My parents had kept his Minidoka paintings in the rafters of the garage.”

You can find the original article by following this link.

Article originally published by The Everett Herald, written by Sara Bruestle. Published Thursday, October 28, 2021