Originally published January 10, 2022 to the International Examiner. Written by Fred Wong.

Cascadia Art Museum’s exhibition (through 2/20/22) of Kenjiro Nomura is a rare chance to see the works of a Japanese American artist that have been nearly forgotten for 60 years. The exhibition wall text provides a good summary, and I’ll quote it in its entirety:

“Kenjiro Nomura

1896 – 1956

American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey”October 21, 2021 through February 20, 2022

We are pleased to present the first solo art exhibition of Kenjiro Nomura (1896 – 1956) in over 60 years. Our three galleries represent highlights from his five-decade career including a selection of rare works by his contemporaries.

Born in Gifu, Japan, Nomura came to Washington State in 1907 and studied with Fokko Tadama in Seattle. He exhibited widely throughout the Northwest and worked as an easel painter for the Public Works of Art Project from 1933-34. He was the first regional artist to have a solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum when it opened in 1933.

During WWII, Nomura and his family were forcibly removed to the Puyallup Assembly Center followed by the Minidoka Incarceration Camp in Idaho. During this time, he produced paintings and drawings of the camps and their activities, many on display in this exhibition.

In 1947, he resumed his painting career with a new focus on abstraction. His painting, ‘The Harbor” was exhibited at the Bienal de São Paulo in 1955, one of the leading international venues of the period.”

The exhibit is arranged into three galleries. The middle and largest gallery features 24 paintings (10 pre WWII and 14 postwar paintings).

One of the other galleries features 21 works from Nomura’s time in the WWII prison camps, Puyallup detention facility and Minidoka confinement camp, and a display case of watercolors, sketch books, two rare paintings in the Japanese style, copy of the Minidoka Irrigator newspaper, other newspaper clippings, and Nomura’s U.S. naturalization documents.

The last gallery features seven early works by Nomura and 14 by his contemporaries including John Matsudaira, George Tsutakawa, Shiro Miyazaki, Paul Horiuchi, Elizabeth Warnanik, Soichi Sunami, Toshi Shimizu, Kamekichi Tokita, Lauretta Sondag, and three from teacher Fokko Tadama, and a display case of early photo albums, documents, paintings and sketches.

Viewing the exhibition is an enriching experience. Reading the accompanying publication, Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey by Barbara Johns, adds to this experience, context, depth and richness. Through her sensitive telling of Nomura’s story, art historian Barbara Johns

“constructs a more inclusive and representative history of American art in Seattle and our nation, and in the process teaches that people of color are not apart but instead very much a part of the fabric of American culture.” Nomura’s life and place in Northwest art well deserve such a book. An outstanding feature is that “this book is exceptionally generously illustrated to create a lasting record.” It is a wonderful read and the index is excellent. A timeline of Nomura’s life would have been an added bonus.

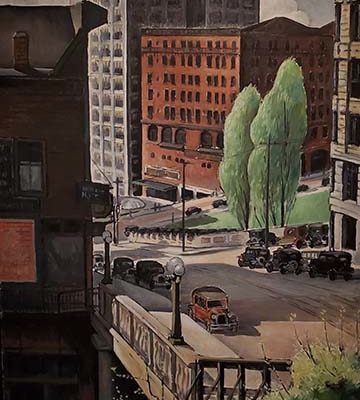

In the large gallery, the paintings from the 1930s show Nomura at the height of his pre WWII artistic evolution. He was a master with a firm grasp of his technique and subject matter. The lines and colors work seamlessly to portray the 1930s urban and rural Puget Sound, the feel, the air, the light, and the ever-present nature.

In his own words, “My desire in painting is to avoid the conventional art rules, so that I can be free to paint and approach nature creatively. I have gradually and almost unconsciously been influenced by the work of early Japanese painters. Now realizing this influence, I am consciously trying to utilize those qualities that I want, such as color, line and simplicity of conception, in my own style of painting. Due to the great difference between the Western style of painting and the Japanese, the problem is a very difficult one, but I am devoting every effort to achieve this.”

He painted mostly places around where he lived, and other places where, as a Japanese American, he felt safe to be.

In the paintings of the 1930s such as Bridge, Untitled (4th Avenue railroad tunnel), and Renton Bridge, nature is an ever-present element, whether it is trees, vegetation, water or clouds. The juxtaposition of the man-made and nature places Nomura squarely as a Puget Sound regional artist. And we are also reminded that “Japanese American artists … have been active here as nowhere else in the country.”

Other distinctive features of Nomura’s paintings are small bright patches of colors, and the depiction of natural light. We are drawn into the patches of bright green, sunlight in the distant landscape, or sunlit building, brickwork, church spire, lamppost, or store front window. Or in the rural paintings like Washington Farm and Red Barn, the siding of the barn, the sun on the cows’ backs, or the reflection in the water.

What I’d love to know, and I wish the exhibition and/or publication provided some historical context for it, is why Nomura and some of his fellow Japanese American artists were so appreciated in the 1930s. What did they do in their art that made their art distinctive, unique? Why were Nomura’s paintings considered “radical” and “one of the new style oil paintings”? Why did Kenneth Callahan name Nomura “one of the leading progressive painters of Seattle”?

After the prison camp in WWII, post war life was extremely difficult. Having lost nearly every material possession, means of making a living, and even sense of safety, Nomura suffered additional personal tragedy. His wife Fumiko “became ill and depressed, and in … 1946, … took her own life.”

Post war, art was likely not a priority in Nomura’s mind. Indeed many of his fellow Japanese American artists who were imprisoned never resumed art making again. This exhibit brings to the fore not only the artistic genius of Nomura, but also the waste of human lives and human potential. Such is a result of this country’s racism and policies, which we must acknowledge and talk about openly. For example, we must tell the full story of people and groups like U.S. Congressmen Henry Jackson and Warren Magnuson, Governor Arthur Langlie, and the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. We must acknowledge the good that they did and also the inhumane, such as when they “campaigned for [the] continued [or even] permanent exclusion” of Japanese-Americans from the Seattle area and Washington State.

Nomura began painting again only after the strong urging and persistent encouragement from friends. From 1947 to the 1950s, Nomura transformed his style to semi abstract and then to fully abstract. I wonder if abstraction appealed to him partly because he was expressing a place that no longer made sense coherently, a place that was no longer recognizable as home.

Regardless of the meaning, his paintings are a visual feast. Puget Sound is a brilliant semi-abstract work that uses the shapes of pilings, beach, walls, water, kelp and ferry, to evoke a familiar scene. Nomura went from using lines for outlining masses to full calligraphic movement. And some of the working methods from the 1930s remain, such as the use of color highlights to draw the eye: the ferry and its watery reflection in Puget Sound, the stop sign in Untitled ([Com]pany), the brick work in An Old Brewery. In the fully abstract paintings, brilliant patches of color draw the viewer in: the red in International Carnival, the orange in Untitled, the yellow in Dragon Dance, the white in Rush Hour and Harbor.

When I walk into the gallery with the Puyallup and Minidoka paintings and drawings, there’s a decidedly different feeling from the earlier artwork before imprisonment. It is not clear to me whether this feeling of drabness or darkness is coming from the color palette or the limited contrast. In these camp paintings, he resumed painting people, who were mostly missing from his earlier or later paintings. And even populated by people, these places do not feel inviting. Camp Harmony is a masterpiece presented like a puzzle, seeming to illustrate the temporary, thrown together feeling of this camp. The Minidoka paintings and drawings capture the climate, sensation, and isolation of living there.

We need to remember that these materials from wartime were a source of pain for many Japanese Americans. “The wartime works with their dark memories remain stored away, carefully bundled and tied as the artist had left them.” In 1991, more than 45 years after the war, when Nomura’s son, “George brought them out of storage (1991), much had happened to change the understanding of the Japanese American Experience.”

The last gallery winds the clock back, so that we can visit Nomura’s early days, and observe some of his contemporaries and influences, and his development of technique and style.

“In 1935 the Seattle Times named Nomura as one of eight artists, and the only one of color, to have contributed significantly to the cultural life of Seattle.” “Nomura’s legacy is that of an immigrant who made his home in the United States and contributed substantially to its cultural life. It is an immigrant experience enriched by his Japanese American understanding and yet constricted by laws, language, and custom. It is an ethnic minority experience, constrained by mainstream assumptions, biases, and social norms… His paintings add meaningfully to an expanded, inclusive view of American art and experience. They are eloquent, present objects through which we interpret and reflect upon not only his time but also our own.”

The exhibition and publication are worthy artistic sojourns and history lessons. We can choose to learn from them and hold ourselves and our systems to a higher standard.

Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey is at the Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonts through February 20, 2022.

You can find the original article through this link.