Published by The Seattle Times, written by Gayle Clemans. Published November 2nd, 2023

Some of the old photographs by Chao-Chen Yang (1909-1969) could have been taken today. They are immediate, tender or funny, and bear no traces of having been created decades ago. Others show telltale signs of their eras: cars or attire from the 1940s or the high-key tones of 1950s color photography.

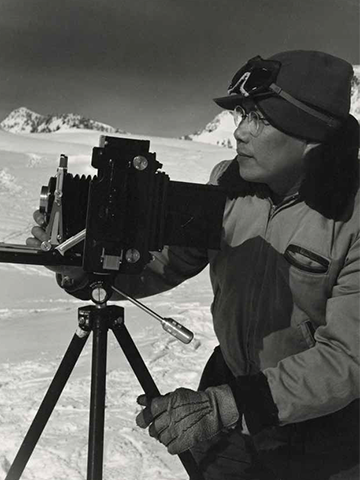

Edmonds’ Cascadia Art Museum has organized the first solo exhibition of this Chinese-born, Seattle-based photographer whose name has been largely forgotten through time. And yet Yang was a nationally recognized and influential photographer for decades, with his images seen widely in exhibitions and on the pages of magazines.

It was shocking to curator David Martin, an expert on Seattle-area artists of the early-to-mid-20th century, when he learned that most of Yang’s work was just sitting in the basement of Yang’s son’s house on Mercer Island. Now, after years of research, Martin has produced a book about Yang (“Full Light and Perfect Shadow: The Photography of Chao-Chen Yang” from University of Washington Press) to accompany the exhibition, all of which is part of the museum’s efforts to recover and highlight the work of important, but underrepresented, regional artists.

A pioneer in the use of color photography in the Northwest, Yang’s journey to Seattle was circuitous. Born in Hangzhou, China, Yang studied painting in Shanghai and then took a government job in Nanjing as an art director. In 1933, he moved to the United States to become chancellor of the Chinese consulate in Chicago and, five years later, transferred to the consulate in Seattle.

With today’s immediate access to cameras on our phones, it’s hard to imagine the deep interest and steep technical challenges that photography generated in the first few decades of the 20th century. Photographic associations sprang up around the country to bring aficionados and professionals together to share knowledge and mount exhibitions. For Yang, the Seattle Photographic Society offered a way to find kindred spirits and to bring his earlier artistic training into his work with the camera.

According to Martin, these artistic groups in Seattle weren’t exclusionary, despite the prejudices prevalent in mainstream culture. “It was very open-minded in these circles. Artists of different racial backgrounds and woman artists — they supported each other. Even artists working within different mediums, sculptors, painters, printmakers, photographers, they all were friends with each other, and they showed in exhibitions together.”

Yang learned about the latest photographic techniques through conversation with other photographers and by reading periodicals. And then he’d set technical challenges for himself: how to capture things in motion, how to amplify contrast between light and dark, how to soften lines and create ambience like the Pictorialist movement, which sought to elevate photography as an art form.

“Apprehension” — one of Yang’s most well-known images — reveals Yang’s aesthetic and technical explorations. A close-up picture of an unknown model gripping a telephone, the photograph was originally created in black-and-white around 1940 and impacted audiences with its dramatic composition and possible narratives. Around nine years later, Yang hand-tinted one of the prints using a Flexichrome kit, a new process developed by Kodak that involved applying layers of color. With his early training as a painter, Yang excelled at this complicated technique and created images that burst with sensitive and saturated colors.

“Apprehension” has also been interpreted in sociopolitical ways, although Yang himself never confirmed any such meaning. The anxiety that exudes from the image has been linked to the experiences of Asian immigrants and Asian Americans during World War II. (Yang was devoted to uplifting the reputation of Chinese Americans and supporting immigrants.) In fact, prior to creating the initial image, Yang had been detained by police on the suspicion that he was a Japanese spy. Another theory suggests that, in the photograph, Yang was alluding to Chinese resistors during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Soon after he left the consulate to focus on photography around 1947, Yang became the director of the Northwest Institute of Photography and taught classes in new color methods such as Flexichrome, dye transfer, and Ektacolor, helping influence countless emerging photographers. Yang also recognized the potential for color photography in commercial projects and created colorful imagery for ads and promotional materials, including his stunning images of Boeing’s latest airplanes.

Like many photographers, Yang would be suddenly struck by spontaneous visual opportunities in the world around him and often created self-portraits as a way to have a figure in the image. With “Solitude,” for example, Yang was moved by the quiet moodiness of a dark, tree-lined sidewalk, punctuated with the glow of street lamps. With no one around, he opened the shutter of his camera, ran into the scene to pose for three minutes, and then dashed back to close the shutter.

This constant and irrepressible passion to create pictures is infused into the body of photographs he created over decades. Yang’s son, Edgar Yang, has donated the collection of several hundred works to the Cascadia Museum and Martin has placed dozens of pieces with other major institutions in Europe and the U.S., including the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

According to Martin, the quantity and quality of Yang’s photographs are a testament to his commitment and contribution to the art form. “He was always busy, always working. He really gave his life to art.”