Originally published Dec. 16, 2021 at 6:00 am. to The Seattle Times. Written by Jade Yamazaki Stewart

A&E Pick of the Week

When Cascadia Art Museum curator David F. Martin first moved to Seattle in 1986, he worked restoring paintings at a small shop in Kent. One day, a man named George Nomura brought in a painting of what looked to Martin like army barracks, though a woman was carrying a bucket of coal beside the buildings.

The man said the painting was his father’s. Even though the painting was severely damaged, Martin recognized its quality.

“Was he a famous artist?” Martin asked.

“Well back in the day, he was, but he’s forgotten now,” the late Nomura replied.

After asking more questions, Martin learned the painter was Kenjiro Nomura, a famous modernist artist in Seattle in the 1930s and early 1940s. And he realized what he thought were barracks were actually housing for some of the roughly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast incarcerated during World War II in America.

Nomura’s blossoming painting career was derailed by his incarceration, and he never regained his prewar fame. Now with an exhibition at the Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds and a new book by art historian Barbara Johns, “ Kenjiro Nomura, American Modernist: An Issei Artist’s Journey,” out this year, Martin hopes the artist will get the credit he deserves as one of the Northwest’s premier modernist artists.

According to Johns’ book, Kenjiro Nomura was born in Japan in 1896 and moved to Tacoma with his parents when he was 10 years old. His parents moved back to Japan with their three American-born children when Nomura was 17. He moved to Seattle’s Nihonmachi (Japantown), founded a sign-painting business and started getting recognized as an artist in his 20s for his modernist paintings of the Seattle cityscape.

In the 1930s, Johns says prominent white Seattle artists and art writers like Kenneth Callahan welcomed Nomura and his issei (first-generation Japanese American) colleagues. (Johns previously wrote books about other prominent Northwest issei artistsKamekichi Tokita and Takuichi Fujii).

Nomura was the first regional artist to have a solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum when it opened in 1933. The same year, one of his paintings was in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1939, his work was included in a world’s fair in San Francisco.

But in 1942, Nomura, his wife Fumiko and son George were forced to leave Nihonmachi — and many of Nomura’s paintings, many of which were never recovered — for the Puyallup Assembly Center (known as Camp Harmony) and later, the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, where they lived behind barbed wire fences, under guard, until the end of the war in 1945.

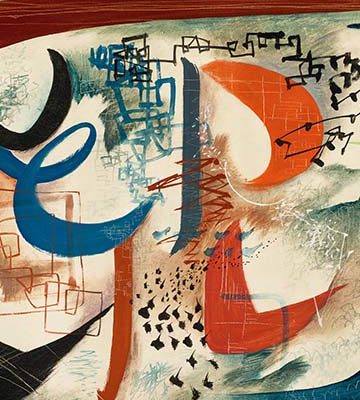

Soon after the war, Nomura’s wife died by suicide, and he fell into a deep depression and stopped painting. He started again after some time, in an abstract style not seen in his previous work, with the support of younger issei artist Paul Horiuchi. But he never regained his prewar fame. Johns says he and other issei artists were left out of the notion of a Northwest School of art, which Callahan had helped form with his writing during the war.

“During the war, they were just out of sight out of mind, seemingly,” Johns says.

Nomura, who became an American citizen in 1954, died two years later.

In 1991, Nomura’s wartime work was exhibited at the Wing Luke Museum and toured across the country the following two decades. But Martin, who’s advocated for Nomura’s work ever since he met his son, said he’s had issues getting major museums to accept Nomura’s work, always getting the same response: that the paintings would better fit in a Japanese historical museum.

This bothers Martin, who views Nomura as an American artist. “He was integrated in the art society here,” he says. “Why should I separate him by his ethnicity?”

When the Cascadia Art Museum opened under his leadership in 2015, Martin knew he’d exhibit Nomura’s work — not as a means to teach Japanese American history, but to showcase his range as an American artist.

The first room of the exhibition is dedicated to Nomura’s early work and that of his contemporaries, mostly scenes from Seattle and the surrounding countryside and nature, painted in a modernist style with Impressionist-inspired constructive brush strokes. The second room shows Nomura’s postwar work — still depicting Seattle, but in an abstract style filled with zigzagging lines, possibly representing energy. Only in the third room does Martin include Nomura’s work from incarceration — including a design for a poster of Camp Harmony he was presumably asked to paint by his imprisoners.

“He was an artist before the internment and after,” Martin says. “I didn’t want him to be pigeonholed.”

Johns says Nomura was somebody who made America, and the Northwest, his home. She believes that, even after being incarcerated, Nomura never rejected his country.

You can find the original article through this link.